Overnight EEG clears up sleep state misperception in insomnia patients, clinicians find. It is also reimbursable.

Recent studies have confirmed that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is a highly effective clinical treatment for insomnia. Typical components of CBT-I include sleep education, sleep hygiene, stimulus control therapy, sleep restriction, relaxation exercises, and cognitive therapy.

Some sleep physicians are employing a new tool to help design the most effective CBT-I intervention for insomnia patients: patient-applied overnight EEG/EOG/EMG devices (“overnight EEG”), which measure indices such as brain waves, eye movements, and muscle movements. Though this at-home objective data gathering may sound similar to the ubiquitous home sleep apnea test, the overnight EEG is not intended and does not screen for sleep-disordered breathing. Clinicians are employing it with insomnia patients to gain insights into their sleep architecture and patterns.

Utilizing Overnight EEG

Robert S. Rosenberg, DO, FCCP, utilizes one such device, Sleep Profiler by Advanced Brain Monitoring, in his practice. Rosenberg is the medical director of the Sleep Disorders Center of Prescott Valley, Ariz, and sleep medicine consultant for Mountain Heart Health Services in Flagstaff. While studying the work of the Penn State Cohort group, he became interested in the high rate of misperception among patients with insomnia. “The researchers were advocating strongly for objective measures such as PSG in evaluating patients with insomnia,” he says. Because Sleep Profiler provides a total profile of types of sleep, including how many times per hour the patient has arousals and from what cause, Rosenberg decided to employ it as an objective measure.

“I had a patient who was sure that he did not sleep more than a few hours a night although his wife disagreed,” Rosenberg says. “He had been on sleep medications for years and had become refractory to them one by one. The Sleep Profiler verified his wife’s observations. He overestimated his time to fall asleep by 90 minutes and his time awake during the night by 120 minutes.” As a result, Rosenberg was able to explain why sleeping pills were not the answer, and that CBT-I, beginning with the fact that many insomniacs sleep much longer than they realize, was the place to start.

Before he began employing overnight EEG, Rosenberg relied on sleep diaries as a guide to treatment. “Sleep diaries are very subjective and recent studies have shown 50% of insomniacs have sleep state misperceptions. They literally can’t differentiate when they are awake versus when they are asleep.” Rosenberg uses overnight EEG initially to give an objective measure of sleep duration and help determine the patient’s sleep restriction therapy. “We know that patients who accurately estimate their time asleep with insomnia, and sleep on average less than 6 hours, have a higher incidence of diabetes, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease. They are also less likely to respond to CBT-I than insomnia normal sleepers [insomnia patients who actually sleep longer than 6 hours but perceive they sleep much less]. It helps me to make decisions about possible pharmacotherapy if CBT-I fails.” “We do not continue to use Sleep Profiler after initial assessment,” Rosenberg adds. “We use sleep diaries. We may use Sleep Profiler in the final week of therapy to calculate progress.”

Charlene Gamaldo, MD, associate professor of neurology and sleep division director at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, recently started using overnight EEG. “We use it for patients who choose to proceed with CBT-I,” she says. “In the past, we relied on subjective methods including sleep logs. I have now found myself shifting toward the sleep all-night EEG monitoring device instead, as I see it as a more specific method to capture sleep-wake physiologic waves and patterns. In patients who would like to explore behavioral strategies for insomnia, we often recommend and offer sleep EEG monitoring to provide objective data regarding their sleep patterns and sleep architecture as a starting point to better understand their sleep patterns and potential disruptors affecting their sleep.”

Gamaldo notes, “We evaluate risk of sleep apnea separately and independently of insomnia. In our current clinic, we use in-lab and Johns Hopkins sleep program designated home sleep apnea devices for those we consider at risk for sleep apnea. We strictly use the sleep EEG all-night device for evaluation and management of insomnia only.”

Rosenberg concurs. “If you take a thorough history and physical, I find that to be unlikely to confuse the two disorders. Besides, in some cases when we are not sure, we test for both.”

Gamaldo appreciates the objective reporting of the at-home device as well. “One patient embraced the idea of having a report that monitored his ‘sleep brain rhythms’ as a guide for pursuing his customized behavioral sleep treatment plan. After 6 weeks of CBT-I, he reported better quality sleep than he obtained in years.”

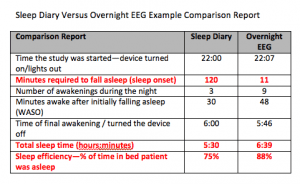

The items in red in this comparison report are indicators of sleep state misperception. The type of sleeping aid one would prescribe is dependent on whether the patient has trouble falling asleep or staying asleep. This patient has sleep onset misperception.

Reimbursement and Rewards

According to Dan Levendowski, president of Advanced Brain Monitoring (maker of Sleep Profiler), the billing code for this procedure is CPT 95827 – Overnight EEG. The procedure has been reimbursed between $450 and $800 in over 2,000 patients and over 40 payors, Levendowski says, with no refusals when billed by board-certified sleep physicians, sleep centers, or neurologists using ICD 9/10 codes for insomnia, hypersomnia, or mood disorders.

To establish medical necessity for an overnight EEG procedure, it is recommended that insomnia patients first undergo an actigraphy study. Those who average more than 6 hours of sleep time by actigraphy have an increased likelihood of having sleep state misperception, and thus are appropriate for overnight EEG study, Levendowski says, adding that the study is recommended to be 2 nights in duration (due to a first night effect) to measure sleep architecture and sleep continuity. The results include a comparison to normative ranges as well as a comparison of the objective measures to the patient’s self-reported sleep quality (via a sleep diary).

At-home monitoring in combination with CBT-I could prove to be a valuable tool for your sleep practice and help bring the reward of healthy sleep to your patients.

[sidebar] Urgency of Effective Insomnia Interventions

Chronic insomnia has been identified as a serious debilitating condition in a variety of ways, many of them unsuspected by both doctor and patient. A recent observational study comparing insomnia patients to matched samples without insomnia revealed the scope of the financial costs.1 Direct costs included inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, and emergency department expenses for all diseases linked to insomnia. Indirect costs included costs related to work absenteeism and the use of short-term disability programs. The study found that the average direct and indirect costs for younger adults with insomnia were about $1,253 greater for 6 months prior to an index date based on the onset of treatment. Elderly adults experienced $1,143 greater costs for insomnia-related expenses.

Insomnia also has been associated with costly workplace accidents and errors. A national cross-sectional telephone survey of commercially insured health plan members assessed workplace accidents and other mistakes costing a company $500 or more in the 12 months prior to the interview.2 The average cost of insomnia-related accidents and errors was $32,062, significantly higher than those of other accidents and errors. Simulations estimated that insomnia was associated with 7.2% of all costly workplace errors and accidents and 23.7% of the costs of these incidents, higher than for any other chronic condition. With annualized US population projections of 274,000 incidents, insomnia-related workplace accidents and errors would have a combined value of $31.1 billion. Yet, that’s just the beginning of the costs related to insomnia.

Many studies have established that insomnia is linked to psychiatric disorders and is a risk factor for the development of depression and anxiety. However, in contrast to the other common sleep disorders, chronic insomnia has not been linked firmly with significant medical morbidity, including cardiovascular disorders. There are, however, recent studies that do show some correlation between some types of insomnia and heart disease.

A Norwegian study provided clear statistical evidence that insomnia is associated with an increased risk of incident heart failure.3 Another study has produced evidence that insomnia associated with short sleep duration is the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder and is associated with cognitive-emotional and cortical arousal, activation of both limbs of the stress system, and a higher risk for hypertension, heart rate variability, diabetes, neurocognitive impairment, and mortality.4 The researchers found that short sleep duration in insomnia is a reliable marker of the biological severity and medical impact of the disorder. The researchers concluded that objective measures of sleep obtained in the home environment should become part of the routine assessment of insomnia patients.—JM [/sidebar]

James Markland has been writing about healthcare for many years. This is his first article for Sleep Review.

REFERENCES

1. Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Walsh JK. The direct and indirect costs of untreated insomnia in adults in the United States. SLEEP. 2007;30(3):263-73.

2. Shahly V, Berglund P, Coulouvrat C, et al. Associations of insomnia with costly workplace accidents and errors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(10):1054-63.

3. Laugsand LE, Strand LB, Platou C, Vatten LJ, Janszky I. Insomnia and the risk of incident heart failure: a population study. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1382-93.

4. Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Laio D, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: The most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(4):241-54.