After identifying a genetic variation in humans that allows a small number of people to get by on less sleep than most, a group of researchers from three universities have developed this variation in mouse models.

Recently published in the journal Science, the study describes a genetic variation found in people who seem to need only about 6 hours of sleep. This genetic variant was then put into mice to create a colony of "insomniac" rodents. Like humans with the variation, called DEC2, mice that received the variant gene appeared to function normally even though they got less sleep than a control group that didn’t have the DEC2 variation.

"We’re all different in many ways, and sleep is one of them," said co-author Christopher R. Jones, MD, PhD, director of the University of Utah’s Sleep-Wake Center. "There may be some people who can function more productively with less sleep."

The discovery of the gene variant occurred after a woman 68 years of age contacted Jones’ collaborators to volunteer for sleep research, explaining that she had an unusually early morning wake-up time. Both the woman and her daughter go to bed between 10 and 10:30 PM and wake up between 4 and 4:30 AM. Yet, the two said that the 18-hour day does not affect their energy levels or ability to function.

"The mom is very energetic and extremely active," said Jones. "In fact, it makes me feel tired to hear about the activities she does every day."

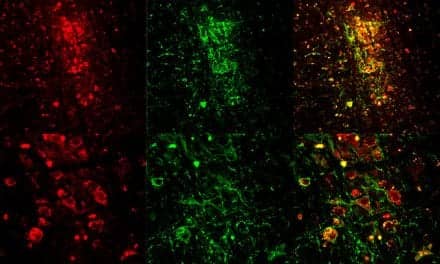

Intrigued by the woman’s ability to operate on less sleep, Jones contacted colleagues at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), who examined the woman’s DNA and identified the DEC2 variation. Those researchers, led by the study’s first and senior authors, Ying He and Ying-Hui Fu, transferred the "insomnia" gene variation into mice to create a colony for study.

The study was then taken over by Stanford researcher Nobuhiro Fujiki and colleagues who measured sleep among the insomniac mice. The researchers monitored when the mice were slumbering, and then interrupted their sleep cycle to see how it would affect them. Even with less sleep, the insomniac mice were more active than a group of control mice that did not have the DEC2 variation. This was determined by monitoring the length of time both groups of mice spent running in wheels inside their cages; the insomniac group spent an average 1.5 hours more turning the wheels than the control group.

While this heightened functioning raised the question of whether the insomniac mice slept deeper than the controls, the researchers monitored their sleep and found it was no deeper than that of the control group.

Jones hopes to study more family members of the now 77-year-old woman. He also wants to explore whether people with the variation are prone to different moods and temperaments than those without it. Do they have more positive outlooks or are they depressed? Are they more driven, and could that explain why they sleep less?

"Their relentless drive is not a mood disorder," Jones said. "There is a strong affective and emotional component to the feeling that you always want to do something. They can’t imagine doing nothing."

Related stories:

Researchers Identify the First Human Gene Implicated in Regulating Length of Sleep