Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center says, “Yes, it can.”

From left, Donald R. Townsend, PhD; Anuja Sharma, MD; Tom Lorentzen, MBA; and Todd Eiken, RPSGT

From left, Donald R. Townsend, PhD; Anuja Sharma, MD; Tom Lorentzen, MBA; and Todd Eiken, RPSGT

Many sleep professionals, at least one major sleep medicine society, and virtually every insurance carrier (including Medicare) have questioned the practice of conducting unattended sleep studies in patients’ homes. Can such tests really be as good as traditional in-laboratory sleep tests, they wonder.

This skepticism, though, has not stopped Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center in St Paul, Minn, from building a patient care algorithm around in-home testing for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Late last year, following extensive research and testing, Metropolitan unveiled what it believes will prove to be a clinically sound and economically viable service model for portable monitoring. Accordingly, this year, the sleep center expects to provide studies at the residences of as many as 1,000 patients—most of whom will pay out of pocket.

“We decided to introduce home testing as an additional testing modality to [polysomnography] because we felt it would be a very good way to meet the growing demand for sleep services resulting from increased awareness of obstructive sleep apnea as a problem in the general population,” says Anuja Sharma, MD, medical director of Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center. “We feel that our model will result in improved access and decreased costs, while allowing us to treat patients in a more timely fashion. We strongly feel that portable monitoring has a place in the diagnosis of OSA.”

Homeward Bound

While the in-home program appears poised to make a significant contribution to the overall success of Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center, it is unlikely to eclipse the enterprise’s lineup of in-laboratory services, which are provided in facilities at five hospital locations across St Paul and the surrounding area. The individual sites are open either 6 or 7 days a week and draw upon the skills of four board-certified sleep medicine physicians, one board-certified sleep medicine psychologist, and 23 technologists.

Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center is operated by St Paul-based Pulmonary & Critical Care Associates, a private-practice group of 13 board-certified pulmonary and critical care physicians that came together in 1980. Metropolitan was launched 17 years later, and today is a popular resource for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) desensitization services, dental appliance referrals, and durable medical equipment. In fact, it was the durable medical equipment component that inspired Metropolitan to consider offering in-home sleep testing in the first place. This began to unfold about 5 years ago, but development of the concept was put on the back burner when it became apparent that the portable monitoring equipment available at the time was inadequate to the task.

“Nothing then on the market could sufficiently measure all the parameters we wanted in the home environment,” Sharma says. “Besides, the technological failure rate of those products was too high.”

That all changed in 2003 when Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center happened upon a newer portable monitor that seemed to fit the bill. “We took a closer look at this home testing technology and quickly realized it was cutting edge, that this was the future, that this was something we should invest in,” says Tom Lorentzen, MBA, chief executive officer of Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center.

Jeanne Lagaly, RPSGT, provides training to Jason McCoy on the home sleep testing device. All home-test patients are trained at the time they pick up the equipment.

Jeanne Lagaly, RPSGT, provides training to Jason McCoy on the home sleep testing device. All home-test patients are trained at the time they pick up the equipment.

How It Works

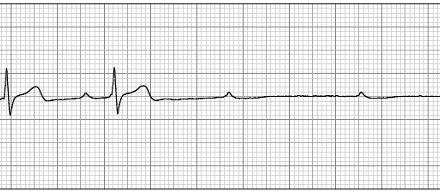

The monitor consists of a wrist-mounted recording unit that collects input from a pair of probes worn on the patient’s fingers. “One of the probes records bursts of sympathetic nervous system activation, which are known to be a very useful marker of arousals,” says Todd Eiken, RPSGT, Metropolitan’s technical director. “The respiratory events during sleep cause or lead to elevation of sympathetic nervous system tone, so, in effect, this device looks at the end result of the respiratory event. Some researchers believe that measuring sympathetic nervous system arousal may be a more sensitive approach than relying on visual review of [electroencephalogram] arousals to detect the degree of sleep disruption.”

The second sensor keeps tabs on the patient’s oximetry. The device also incorporates an actigraph and measures heart rate. “It uses a complex proprietary algorithm to determine sleep and detect respiratory events,” Eiken says.

Accumulated data from the device are stored on a flash memory card in the recording unit. The following day, the data are uploaded from the card into a computer at Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center headquarters.

“Our computer contains software that analyzes all the tested parameters to detect various types of respiratory events during rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep,” Eiken says. “Additionally, our physicians can review the raw data to further explore specific events, just as is done with conventional PSG studies.”

Importantly, the monitor is designed to be used by the patient without an attendant present. “The device is very easy to operate,” Sharma says. “The patient places the probes on his or her fingers and then pushes the ‘on’ button at bedtime. It is that simple.”

The patient must come to the laboratory to pick up the monitor. (Training in its use is provided at that time.) It also is the responsibility of the patient to return the unit to Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center as soon as the test is completed. This approach lets Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center avoid a host of logistical challenges and costs, ranging from the juggling of technologist schedules to the not-inconsequential matter of ensuring the safety of employees as they travel to and from the patients’ homes and during the time they are present there, Lorentzen says.

Donald R. Townsend, PhD, investigated the reliability of home testing for patients such as Valerie Kjellberg.

Donald R. Townsend, PhD, investigated the reliability of home testing for patients such as Valerie Kjellberg.

Appropriateness Screening

Although various journal articles gave good marks to this technology and its ability to diagnose sleep apnea in an alternate unattended setting, Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center nonetheless decided to conduct a stringent review of its own before launching the in-home program. “We wanted to test in-home patient outcomes, side by side, against those of conventional, in-laboratory PSGs, so we took 103 new sleep patients and randomly assigned them to one or the other type of study,” says Donald R. Townsend, PhD, director of behavioral care and research at Metropolitan. “Our expectation was that we would find no significant differences between them, and, by and large, that is precisely what happened. Patients had equally good outcomes whether they were diagnosed in the laboratory or in the home environment. This was true of virtually all the outcomes measures we looked at. We became convinced by this that in-home testing—under the right circumstances, with the right direction—was useful and represented a viable model for the future.”

Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center’s researchers presented the results of their study at last year’s Associated Professional Sleep Societies (APSS) sleep conference and subsequently have submitted a paper to a leading medical journal. “We uncovered no problems unique to home testing,” Townsend offers in summary of that paper’s findings.

Anuja Sharma, MD, says home testing may improve access to sleep testing.

Anuja Sharma, MD, says home testing may improve access to sleep testing.

In day-to-day practice, with the in-home program now operational, the procedure for ordering a home-based study is almost identical to that of one conducted at the laboratory. “There is a rigorous pretest evaluation to assess the appropriateness of home testing and using the equipment we offer, as well as to acquire the medical history needed to produce a correct diagnosis,” Townsend says. “Basically, the patients we test at home are those with cardinal symptoms of sleep apnea and who have the least number of comorbid medical conditions or alternative explanations for their symptoms.”

Those who qualify for in-home testing seem to appreciate the convenience and comfort it affords, Eiken reports. Their satisfaction is heightened by the fact that they are assured of being seen by a sleep physician at the time the monitor is brought back to the laboratory. “This way, we can give the diagnosis and, if warranted, begin treatment before the patient leaves our facility,” he says.

Insurance Work-Around

Patients may be happy with this arrangement, but the same cannot be said of all payors. “Some insurers see in-home testing as a service not sufficiently proven,” Lorentzen says. “Medicare, for example, not long ago announced it was unable to make a determination about the validity of in-home studies, because there was not enough evidence involving the senior population, among other reasons—and since most payors in Minnesota tend to follow Medicare’s lead, well, you can see where that leaves us.”

Lorentzen indicates that Metropoli-tan Sleep Disorders Center has not abandoned hope of ever changing the thinking of private payors in the state, but admits the enterprise faces a heady challenge in its attempts to do so. “We have presented our study results at [the American Academy of Sleep Medicine] and look forward to publishing our paper this summer,” he says. “It is our hope that our study results and subsequent outcomes will move insurers to reconsider their position.

Ordinarily, insurer refusal to reimburse would spell doom for a fledgling service line such as this. However, Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center has crafted a satisfactory work-around. What the laboratory does is offer in-home studies at a reasonable enough price that most patients not covered for such studies by their health insurance plan can afford to pay entirely out of their own pockets.

“On our home studies, we charge less than what most patients would normally spend on an insurance-covered co-pay for an in-laboratory PSG,” Lorentzen says, explaining that such is possible because the cost to perform an in-home test using the portable monitor is appreciably lower to begin with than an in-laboratory study. “To produce a diagnosis using portable monitoring technology costs an average of $653. Factored into that sum are all the associated costs of the equipment, plus the expense of having to restudy in the laboratory the 10% of home patients whose test results turn out to be inconclusive or invalid. By contrast, the study and subsequent steps to arrive at a diagnosis using in-laboratory PSG cost an average of $2,181.”

Better Compliance

Another advantage to in-home testing is it sets the stage for better compliance with therapy, Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center believes. Even so, laboratory officials recognize that compliance is never a foregone conclusion; indeed, it is an issue Sharma and her team know they must work hard at. “Among the things we are doing to improve compliance is educating patients and providing them with the fullest set of resources they need to achieve a good outcome,” Eiken says. “For example, as part of our durable medical equipment component, we have CPAP specialists available to provide assistance to patients. We also have a very substantial CPAP follow-up program that employs multiple phone and office encounters.”

That CPAP follow-up program, by the way, stretches across a period of about 10 weeks. “During that time, we help the patient with everything from their CPAP mask interfaces to home equipment inspections,” Eiken continues. “We have identified an entire list of potential problems that can interfere with compliance. And, having identified those, we also have developed procedures that our CPAP specialists can follow to make sure those problems are resolved.”

Compliance is a challenge, but the bigger one for Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center revolves around simply being able to meet the growing demand for sleep services—a demand arising in no small part from the spread of success stories told by Metropolitan Sleep Disorders Center patients.

“There is more to it than just favorable word of mouth about us,” Lorentzen says. “Awareness of sleep apnea is increasing in general, and that too benefits us—just as it benefits laboratories everywhere. In fact, I think this growth in awareness is going to prove to be a driver that ultimately prompts more and more laboratories to look into testing at home as a way to accommodate all who seek help with sleep disorders. Perhaps within the coming 5 years, it might be the case that uncomplicated sleep apnea studies performed in the laboratory will be the exception rather than the norm.”

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Sleep Review.