A sleep lab manager shares how his center is navigating the difficulties of testing and treating patients for sleep disorders during a pandemic.

By Henry L. Johns, RPSGT, CRT, CPFT

We have all been faced with a challenge we never thought we would see. After an almost three-month shutdown, how do we safely reopen our sleep labs in the middle of a pandemic? No matter if you have a hospital-based or freestanding sleep lab, the challenge is the same: What do we need to consider for reopening, and most importantly, to maintain the trust of our patients and communities?

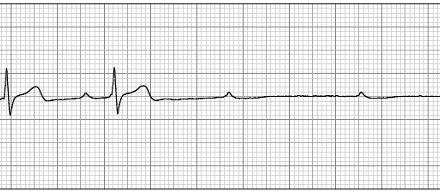

SARS CoV-2 is a highly contagious disease that primarily causes respiratory distress. It is easily spread by airborne droplets from a cough or forced exhalation. Since the use of CPAP could possibly produce a steady stream of exhaled particles, we must take precautions for the safety of patients and staff.

Here is what I tried to consider when the time came to reopen our lab.

Updating the Bedrooms

Best practice is to use negative airflow rooms, also called isolation rooms. But most sleep labs do not have this capability or even an HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) system robust enough to exchange air as often as recommended. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, evidence is growing that this virus can remain airborne for longer times than previously speculated and travel distances of more than 6 feet.1 A study published by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in July 2020 reports that numerous cases of COVID-19 occurred in Guangzhou, China, in February 2020 due to droplet transmission through the building’s air conditioning system.2 This is also suspected in the Diamond Princess cruise ship cases.3

We considered converting some, or all, of our bedrooms to negative airflow; however, we quickly discovered it would be cost-prohibitive. What’s more, the negative flow units we researched were extremely noisy—and would not lend themselves to letting patients sleep. Our building’s HVAC system does not allow for any additional air exchange with the outside or additional filtration behind the hospital-grade filters that were already in place. Since our lab has 4 bedrooms and would be using no more than 2 per night, we have opted to rotate rooms to allow for the time needed by the HVAC system to exchange the air in the room several times.

Recommendations for room air exchange to help reduce transmission of the virus include:

- increase ventilation with outdoor air and increase air filtration measures (this is sometimes difficult in commercial buildings);

- use portable air cleaners with high efficiency particular air (HEPA) filters to supplement increased HVAC system ventilation and filtration;

- direct airflow so it does not blow directly from one person to another (many sleep labs use fans for patient comfort and should review their use and location of them); and

- rotate room use to allow at least 24 hours of down time between uses.

Protecting Staff & Patients

Another important consideration to reopening is the anxiety of patients and staff about COVID-19 transmission. We have all been under a lot of stress over the past few months. It is especially important to try to reduce any fears people have when they come into the lab. A high percentage of our patients (and in some cases, staff) are in high-risk categories due to age or comorbidities. Careful screening is an important factor, along with access to COVID-19 testing.

[RELATED: What’s Next for Sleep Disorders Centers?]

Since PAP will most likely be used during the night, it is helpful to have patients self -quarantine before their scheduled sleep studies, and I would strongly urge you to consider COVID-19 testing for patients (no more than 72 hours prior to the sleep study). Patients who test positive for the virus should have their sleep studies postponed.

Staff should use standard personal protective equipment (PPE), including masks and face shields, during sleep study equipment hook up. If the patient has not had a COVID-19 test or there is a chance of exposure, the staff should use full PPE, which means an N-95 mask, face shield, gown, and gloves. Donning and doffing PPE should take place outside of the patient room.

Our staff members use N-95 masks three nights in a row (unless soiled), covering the N-95 with a surgical mask (which is discarded after each shift) to help protect it. Each week, the N-95s are sent for reprocessing and returned to the lab. So far, it has not been necessary to use the reprocessed masks. Face shields are always worn when working directly with the patient. Gowns are only used if there is a COVID-19 presumptive positive due to symptoms or for staff comfort.

We use a supply system that requires staff members to log in for access. It allows for more accurate tracking of PPE usage. With PPE in short supply in many areas, strict monitoring may be necessary to conserve your supply.

Additionally, because of the possibility of inadvertent spread of virus, sleep testing should be limited to one-on-one care. This is not the most cost-effective practice for a lab, but it may be the safest option during the pandemic. As part of our reopening plan, our lab is functioning at 50% capacity until December. Hospital-based labs and labs with an associated durable medical equipment arm may find this easier financially than an independent lab that depends on a higher review stream. In many cases, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reimbursement covers sleep lab space, equipment, supplies, and staff, but leaves little or no margin.

Our lab is fortunate to have a top-notch environmental care (housekeeping) crew. The bedrooms are cleaned thoroughly each day and allowed to remain dormant for a night before the next use. We have shifted all daytime testing and multiple sleep latency testing (MSLTs) to days without nighttime use since we are not currently sleep testing 7 nights/week.

To summarize, precautions to protect patients and staff include:

- telling patients to self-quarantine and requiring a negative COVID-19 test result within 72 hours of a sleep study;

- screening patients and staff upon arrival each day, using a no-touch thermometer to check temperatures and asking if they are experiencing common symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, flu-like symptoms, loss of taste or smell, body aches, nausea, fatigue, or headache;

- using disposable PSG sensors, belts, and electrodes (almost 90% of our lab’s are disposable);.

- terminally cleaning bedrooms each day (your housekeeping staff are important team members);

- and extending wait times between room uses to allow ventilation.

What About CPAP?

The risk of a PAP generator blowing a continuous stream of virus-laden particles into the air is frightening. Although there are no COVID-19-specific cleaning recommendations for PAP devices for, the best we can and should continue to do is to follow the manufacturers’ recommendations for cleaning.

In our lab, we wondered about the air intake on the device and the possibility of the blower becoming contaminated, as well as possibly entraining virus and sending it straight into the patient.

[RELATED: How Is the Coronavirus Impacting Sleep Medicine Professionals?]

To help reduce risk, workable measures include:

- replacing intake filters with HEPA filters (we cut material from an N-95 mask to fit the intake opening, which is changed between patients; although not perfect, it is better than no inlet filer at all);

- discontinue the use of humidifiers (this was done because of the use of bacteria/viral filters);

- using bacteria/viral filters on the circuit;

- using disposable tubing and interfaces.

Increased Role of Home Sleep Testing

Home sleep tests (HST) have taken on a more important role since in-lab testing has been reduced due to the pandemic. In our lab, about a third of patients qualify for HST each week. We use standard inclusion criteria, with some additional exclusion criteria tailored to our patient population.

We handle instruction in person, although many labs have existing mail-out programs that allow for remote instruction and contact-free device delivery. The biggest challenge for HST is how to handle and clean the equipment. Again, we use disposables as much as possible. The unit is then cleaned using a viricidal wipe and allowed to remain idle for 24 hours. [Editor’s Note: The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends at least 72 hours of idle time between uses.4]

Practices to lower risks of virus spread via home sleep testing include:

- using disposable belts and sensors;

- disinfecting per manufacturers’ recommendations;

- ensuring at least 24 hours of idle time after disinfection before the next use;

- use of autoPAP where applicable for HST patients with obstructive sleep apnea (our lab brings in severe OSA cases for a full titration).

Also, some vendors are now offering totally or mostly disposable HST equipment now.

Take Home Messages

There is no perfect way to navigate the times we are in, but we can make things as safe as possible by instituting a few measures. Check in with your staff often to find out what works and what does not. Keep up with the latest from the CDC and state health agencies. Air exchange and filters in rooms, screening for symptoms, and COVID-19 testing are all part of a wider strategy that includes social distancing, masks, handwashing, and surface disinfection. We all hope that within the next 12 months an effective vaccine will be developed. The combined strategy of in-lab PSG and HST may help many labs survive. As we learn more, we are better able to respond to our new normal.

Henry L. Johns, RPSGT, CRT, CPFT, is a supervisory program specialist at the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Eastern Kansas Health System.

References

- hUnited States Environmental Protection Agency. Indoor Air and Coronavirus (COVID-19). 16 July 2020. Available at www.epa.gov/coronavirus/indoor-air-and-coronavirus-covid-19

- Moses FW, Gonzalez-Rothi R, Schmidt G. COVID-19 Outbreak Associated with Air Conditioning in Restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2020;26(9):2298.

- Correia G, Rodrigues L, Gameiro da Silva M, Gonçalves T. Airborne route and bad use of ventilation systems as non-negligible factors in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Med Hypotheses. 2020 Aug;141:109781. Epub 2020 Apr 25.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Considerations for the practice of sleep medicine during COVID-19. 27 Aug 2020. Available at aasm.org/covid-19-resources/considerations-practice-sleep-medicine

Photo 178948729 © Frank Armstrong – Dreamstime.com