Dental sleep medicine practitioners share strategies for ensuring obstructive sleep apnea patients who opt for oral appliance therapy are titrated in sleep centers.

Most Thursday and Friday nights, sleep technologists in northwest Arkansas can smell him coming.

“Whenever I go into the labs, I try to carry something for the sleep techs to eat. Chicken nuggets are my favorite. Whenever I can I try to feed the techs—I want them to love me!” says Ken Berley, DDS, JD, DABDSM.

“For Christmas, I take chocolate candy and popcorn treats for the techs too,” adds Berley, who enjoys privileges at four sleep labs near his Rogers, Ark, dental practice. “And, I’ll tell you what, the dentists who are not doing this are missing out.”

These treats are a small thing, but they help Berley, a dental sleep medicine practitioner as well as a licensed attorney-legal consultant to other dentists, cultivate an increasingly important relationship that all dentists who treat patients with oral appliances should develop: bidirectional access for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients from dentist’s chair to sleep center bed and vice versa. According to Berley, “A positive relationship with local sleep labs is a key factor in developing a successful referral practice.”

Oral appliances typically treat OSA by holding a patient’s lower jaw open and slightly forward during sleep, which prevents an obstruction of the airway; it’s a mechanism similar to the jaw-thrust maneuver employed during cardiopulmonary resuscitation or CPR.

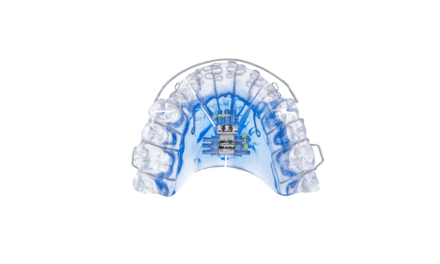

But most prescription oral appliances—of which there are more than 100 and counting with FDA clearance in the United States1—must be custom fitted by a qualified dentist, who ensures the device is efficacious and reasonably comfortable for the specific patient. Finding the correct setting in millimeter increments can be accomplished in three ways, each of which can be used in conjunction with the others: having the patient alert the clinician to subjective improvements, a low threshold that does not necessarily correlate to objective outcomes; having the patient perform one or more overnight sleep tests at home using a home sleep testing (HST) device while trying the oral appliance at different settings; and/or titrating the oral appliance overnight in a sleep disorders center bed, with a sleep tech gradually adjusting the settings until the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) reaches a clinically acceptable level—the latter generally regarded as the best option from both clinical and liability standpoints.

A challenge for many dentists lies in cultivating that bidirectional sleep lab relationship. Some approach sleep center managers only to find them hesitant to do overnight oral appliance studies in their labs. Sleep lab managers and sleep techs do face obstacles when accommodating in-lab polysomnography (PSG) for patients with oral appliances. These range from unfamiliarity with the myriad oral device makes and models to hesitation to awaken the patient multiple times to turn the device’s titration screw (which in most oral appliances is located inside the mouth, so it isn’t accessible when the patient is asleep) when they typically do positive airway pressure titrations that can be fully completed while the patient remains asleep.

Hence, the chicken nuggets. Berley, an ABSDM Diplomate, uses them as one tool to overcome hesitation to ensure oral appliance patients are welcome at local sleep centers. He employs many other techniques as well, including accepting the sleep centers’ CPAP-failing patients to his dental practice. “Understand, sleep labs are a great referral source,” says Berley. “The sleep techs will be in there with somebody who is not responding well to CPAP [continuous positive airway pressure], and they throw their mask across the room. It is important for the sleep techs to understand that I can help these patients.”

Titration Nuts & Bolts

For Berley to personally be present for every oral appliance titration, he requires that the patients schedule their sleep lab titration PSGs on Thursday or Friday nights as Berley does not see patients in his office on the following days. This strategy is one that other dentists can consider emulating. Berley attempts to schedule as many patients in a lab on a given night as possible, sometimes filling an entire sleep center with oral appliance patients alone.

The sleep techs do help with the titrations, but Berley typically makes the decision when to titrate. He has found that most techs want to titrate the appliance too frequently. “Every time the patient has an event they want to go into the room, wake that patient up, and do a titration. But you can’t do that. Since you must wake the patients up in order to titrate them, it is ideal to titrate the patients after observing a full REM cycle. Although that is not always the case if I am observing a significant number of events in stage 2, but I try to let the patient sleep until I see a full REM cycle.” The goal is to wake the patients up as few times as possible. Because of that, Berley uses in-office titration testing to get the patient as close to normal as possible before going back to the lab for final PSG.

“Many dentists want the techs to titrate their patients instead of doing it themselves,” continues Berley. “Been there, done that. It doesn’t work. If you have a really, really trained RPSGT, then maybe….But we have 153 FDA-approved oral appliances out there. And if you have a tech do the [titrations], I don’t care how specific your written instructions are, things can go wrong.

“I have frequently seen patients with one side of the appliance protruded and the other side retruded. The techs just don’t have the experience to handle the problems that occur with oral appliances, which often include: loose appliances that dislodge and must be tightened, Herbst screws coming loose, positional aids used incorrectly, and the need for new Herbst bars or other advancement issues. Techs just don’t have the training and sometimes the tools to consistently get good results when titrating these appliances.” In Berley’s opinion, titration of these appliances is the dentist’s responsibility. He rhetorically asks: If the dentist is not present in the lab and the titration fails or the study fails because of a lack of titration, who pays for the next study?

In Berley’s opinion, it is mandatory to use an HST or pulse oximetry for in-office titration to ensure that your patients’ AHI is below 10 before they are referred back for a final PSG. He says this allows for fewer in-lab appliance adjustments.

Berley shares his three main goals for oral appliance titrations: “Goal number 1: The patient must wear the oral appliance all night every night. Goal number 2 is to titrate the appliance adequately to eliminate the subjective symptoms. Goal number 3 is to titrate the appliance for maximum medical improvement and resolution of the objective symptoms. The problem is the patient has felt bad for so long they are going to start feeling better quickly after appliance insertion and the dentist may stop titrating the appliance too soon. Frequently, titration is terminated based on subjective symptoms and the patient’s objective symptoms remain unresolved. With HST-guided in-office titration which is confirmed and tweaked in a final PSG, consistently good results are obtainable.”

Here, it is important to note that dental insurance plans do not cover PSGs, or oral appliances for OSA for that matter. Instead, these services are covered by the patient’s medical insurance plan, including Medicare, and typically only when deemed a “medical necessity” by a sleep physician. While some dental sleep medicine practitioners opt to have their patients pay out-of-pocket for the oral appliance itself versus learning how to do medical insurance paperwork, having a patient pay out-of-pocket for a PSG will be cost-prohibitive for most. So dentists who do not yet have a plan for medical billing will need to develop one prior to sending oral appliances patients in-lab.

Berley believes that all dental sleep medicine procedures should be filed on the patient’s medical insurance (which may be Medicare). Because OSA is a medical condition, dentists should never attempt to file these procedures on the patient’s dental insurance. With simple instructions, any dental office can master filing medical insurance, Berley says. (Sleep Review’s view is the patient should have the option to file the device and any related services with their medical insurance. There are firms that specialize in medical billing for dentists to which dentists can outsource this work.)

An Alternate Approach: Provide Sleep Techs with a “Cheat Sheet”

In south Florida, Kenneth A. Mogell, DMD, DABDSM, realized early in his dental sleep medicine career that proper communication is essential between all of the disciplines “in the sleep community” including physicians, dentists, sleep techs, and respiratory therapists.

While he anticipated resistance from referring physicians to the idea of using oral appliance therapy on their patients with sleep apnea, he was taken aback by how many cited a lack of communication from dentists about their patients following past referrals. “I referred my patients to the dentist and they fall into a black hole and I never hear from them again!” one sleep physician lamented, says Mogell, a member of the Sleep Review editorial advisory board who recalled the incident in an article he penned in 2016.2

The colorful proclamation would help Mogell remember the lesson he’d learned about the value of multidisciplinary communication, which he determined to put into action as he began his practice.

He began writing letters periodically with updates on patient progress for physicians. Eventually, he would develop several templates for the letters to address the many communication needs of a thriving referral-based dental sleep practice, including a letter to request an oral appliance titration PSG. This letter purposely includes the make and model of the oral appliance, a photo of the appliance, what setting the appliance is currently on, and how many turn options remain.

What’s more, he gives each sleep lab a demonstration model of each oral appliance he employs, as well as the corresponding advancement wrench (in case the sleep-deprived patient forgets to bring theirs to the lab). Finally, he devised a “cheat sheet.” The laminated poster has a photo of each device Mogell uses in his practice, and under each photo is the device’s name and hints for how to titrate it. (For example, “Dorsal Fin Type: Every turn is 0.1 mm. 10 turns = 1 mm. Appliance can be advanced to 6.0 mm or 60 turns.”) He includes his phone number at the bottom and lets the sleep techs know he is “on call” remotely should questions or concerns arise.2

Utilizing HST Pre-Titration PSG

All of Berley and Mogell’s sleep apnea patients are referred to them by sleep physicians. Most of the patients have already failed CPAP.

Although dentists can’t diagnose sleep apnea, many use HST or pulse oximetry devices to conduct preliminary therapy efficacy checks. Some practitioners are adamantly opposed to dentists utilizing HST for any reason.3 But Berley finds that conducting titration HST studies is essential. “Frequently I am referred a patient who has an in-lab PSG that is obviously incorrect. This can be due to first night effect or any other reason. Those patients get an HST in their bed before we begin therapy. By the time the patient is referred to the lab for a follow-up PSG, they may have had several HSTs, depending on the severity of the patient. This allows for easy in-lab final titration.” In this way, by the time Berley refers patients to a physician for final PSG, he is aware the oral appliance is objectively working.

“All of my sleep physicians know that I have HST, and they encourage me to use it. Because once I get the patient ready to go to the sleep lab, it is a minor type of titration,” he says. “The basic titration occurs in my office to get them ready to go back to the sleep lab. And then it’s just one or two times I interrupt them in the night for titration.

“If you don’t get [patients] ready for a PSG with HST, you’re going to be too aggressive in the sleep lab when you are titrating them. You cannot advance a patient 3, 4, or 5 mm in the sleep lab; it’s too much.

“Ultimately, HST is a tool,” says Berley, who emphasizes that dentists should not be in the business of diagnosing OSA. “We want to be a part of the team who provide treatment for OSA. As a member of a healthcare team where the sleep physician is the quarterback, we all share liability for a bad outcome,” he says. “Remember, I am the dentist-attorney.”

Chuck Holt is a Florida-based freelance writer and editor.

References

1. AADSM. Oral Appliance Therapy: About oral appliance therapy. ND. Available www.aadsm.org/oralappliances.aspx.

2. Mogell K. Stellar communication for the dental sleep medicine practitioner. Sleep Review. 2016 May 9. Available www.sleepreviewmag.com/2016/05/stellar-communication-dental-sleep-medicine-practitioner

3. Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, Lettieri CJ, Chervin RD. Recommendations for oral appliance therapy collaboration to treat obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Review. 2016 Oct 10. Available www.sleepreviewmag.com/2016/10/recommendations-oral-appliance-therapy-collaboration